More than fifty years ago, a group of teachers and scholars made history. In 1974, the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) passed a resolution that sounded simple but was revolutionary: students have a right to their own language.

This statement, known as Students’ Right to Their Own Language (SRTOL), challenged the idea that only one kind of English (the “standard,” polished, academic kind) was legitimate in the classroom. It called for schools to respect the diverse ways people speak and write, especially those shaped by race, class, and culture.

Half a century later, that dream is still unfinished.

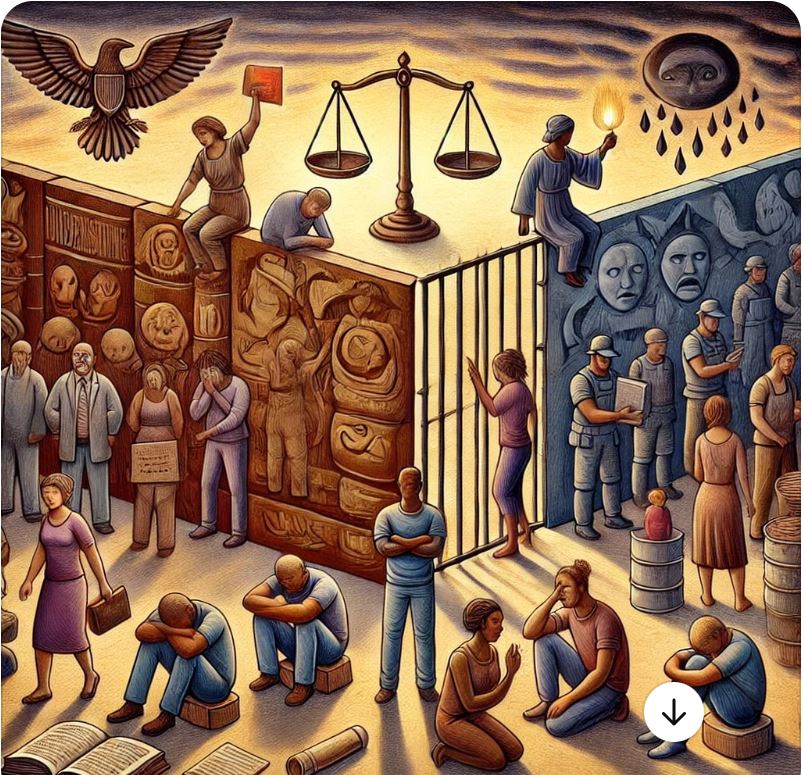

Even today, many students—especially multilingual, immigrant, and international students—find that their voices are “corrected” into silence. Their linguistic differences are treated as mistakes instead of strengths. And the higher they climb in education, the more pressure they feel to sound a certain way: “academic,” “professional,” and often, “white.”

Why the Old Way Still Holds Power

For a long time, language teaching has been built around what linguists call interlanguage: the idea that students learning English are moving along a path from their “broken” or “nonstandard” language toward the correct, standard one.

At first glance, that doesn’t sound terrible. It assumes learning is a process, not a failure. But in practice, this way of thinking keeps standard English as the ultimate goal, and everything else as an error to fix.

When professors say they’re helping students “improve their clarity” or “sound more academic,” they often mean “sound more like me.” The result? Multilingual and international students spend more time repairing their sentences than exploring their ideas. Their writing is seen through a deficit lens, as something lacking, rather than as a powerful form of expression rooted in cultural and linguistic richness.

That’s how higher education, often unintentionally, continues to reproduce the very assimilation SRTOL was meant to challenge.

Translanguaging: A More Human Way of Seeing Language

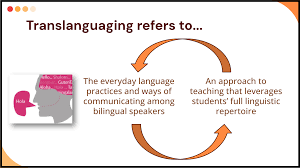

Enter a newer idea—translanguaging.

Instead of dividing language into categories like “first” and “second,” translanguaging views all of a person’s languages, dialects, and communicative styles as one connected system. A Nigerian student who switches between Yoruba, Nigerian English, and American English in one conversation isn’t “code-switching” between different languages, rather, they are using their full linguistic toolbox to make meaning.

Translanguaging invites teachers to see that toolbox as a gift, not a problem. It shifts the question from “Is this English?” to “What is this student trying to say, and how can their full linguistic and cultural knowledge help them say it?”

More importantly, translanguaging isn’t just about teaching strategies; it’s about power. It directly challenges the idea that there’s one correct way to speak or write. It asks institutions to honor the fluid, creative, and political ways students actually use language in real life.

In classrooms where translanguaging is embraced, students stop “performing correctness” and start performing confidence.

Why SRTOL Still Hasn’t Fully Taken Root

So if we’ve had decades of scholarship supporting linguistic diversity, why does SRTOL still struggle in practice?

There are a few stubborn reasons:

- Institutional bureaucracy. University policies, grading rubrics, and even syllabi act like what sociologist Dorothy Smith calls boss texts (documents that quietly enforce standardization and power).

- The myth of clarity. “Standard English” is defended as a matter of fairness, but “clarity” is often defined by those in power.

- Safe diversity. Institutions like to celebrate “multilingualism” in brochures, but not in literate practices. Linguistic justice gets reduced to a buzzword.

- The persistence of interlanguage thinking. Many instructors, even well-meaning ones, still treat language difference as a step toward a norm rather than as a different kind of norm altogether.

Until these deep-seated ideologies shift, SRTOL will remain more of a statement than a practice.

From Language to Literacy: A Bigger, Fuller Vision

Maybe the issue is that we’ve been thinking too narrowly about what “language” even means.

What if we thought instead about Students’ Right to Their Own Literacy?

Literacy goes beyond the words we write or say. It includes gestures, silences, tone, storytelling traditions, and the lived experiences that shape how people communicate. For many international and diasporic students, literacy is an embodied practice; it includes the ways they navigate power, identity, and belonging in spaces that were not built for them.

Recognizing this means valuing the how of communication as much as the what. It means reading silence not as disengagement but as reflection. It means seeing multilingual writing as a form of world-making, not world-breaking.

Students don’t just need permission to bring their languages to school, they need institutions that see those languages as knowledge.

A Call for Change (?)

If we truly believe in Students’ Right to Their Own Language, then our classrooms and policies must reflect it.

That means:

- Welcoming assignments that mix languages and genres.

- Grading for thought and effort, not just grammar and form.

- Encouraging writing that sounds like real people, not artificial “academic” voices.

- Training educators to see multilingualism as power, not deficiency.

Translanguaging offers us a way forward—a way to see language not as a barrier to overcome but as a bridge to understanding. It’s time to move SRTOL from a slogan to a lived reality. If we cannot, let’s stop pretending altogether and just own up to the hypocrisy that our classrooms value a certain kind of correctness more than connection. Justice in education cannot exist without linguistic justice.

Ire o!

In Conversation With:

Bloome (2009); Canagarajah (2015, 2019, 2020); Guo (2022); Hall & Cook (2012); Horner, Royster, & Trimbur (2024); Inoue (2019); Kinloch (2005); LaFrance (2019); Liu (2023); Parks (2000, 2013); Perryman-Clark et al. (2015); Smith (2002, 2005, 2006); Smitherman (2003); Wei & García (2022); Yeager & Green (2009).

Leave a comment