As the instructor of record for a university pathway course, “First-Year Writing,” I teach my students how effective writers adapt their writing to various situations, both within and beyond college. I emphasize that successful writing involves understanding what makes a piece effective and knowing how to use specific techniques, strategies, and concepts to develop versatile and capable communication skills. One of the major projects in this course is titled “Literacy Narrative.” In this project, students are required to describe how their conception of literacy developed and the factors that influenced it.

Perhaps due to the culture I grew up in, where non-schooled individuals, especially elders, are literate in other significant ways, I have never believed that literacy is limited to the traditional concept of reading and writing. When I ask my first-year students what literacy means, their answers almost always focus on the ability to read and write. It’s disheartening that, in a world full of endless possibilities, students are not exposed early enough to the diverse ways of knowing beyond classroom learning. The positive side, however, is that while they come into my class with this narrow perspective, they leave with a new understanding of other forms of knowledge and aspects of human experience that also count as literacy. They truly appreciate this shift, as it allows them to see themselves beyond the rigid expectations of institutional definitions of success.

When I design the assignment description for this project, as well as the supporting in-class activities, my students are encouraged to be open-minded and try to recall any activity they are involved in that could count as literacy. I must say, the results are usually beyond my expectations; these students take me to literacy spaces I never knew existed or even thought possible. Recently, two students from different sections of my class wrote about emotional literacy. One wrote about how their decision to forge ahead in life after losing their mom—the most important person in their life—is a kind of literacy. Another described how their ability to gauge people’s feelings has helped them thrive in different areas of their lives.

This brings me to the crux of my message in this write-up.

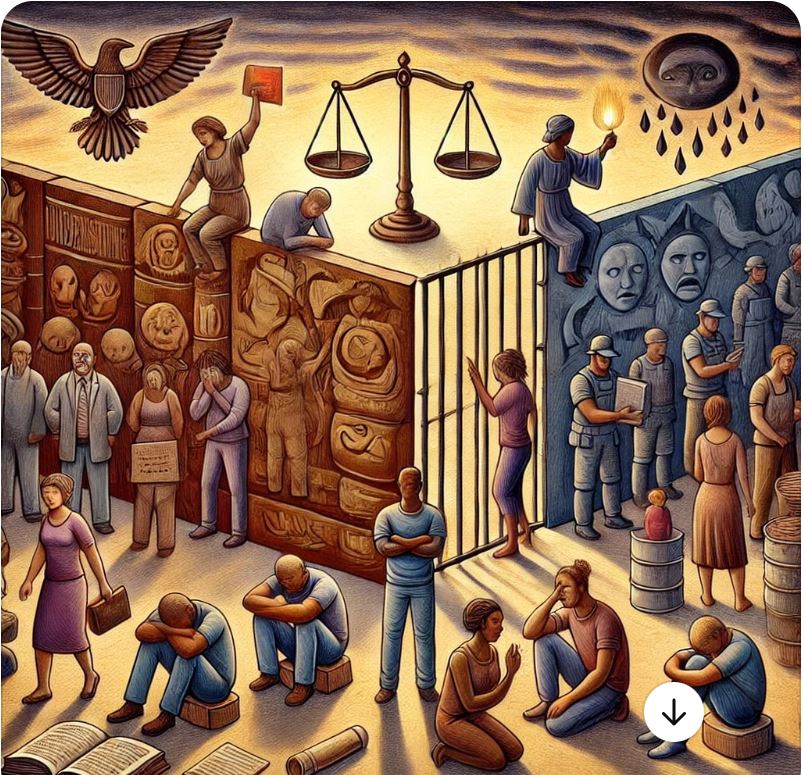

As someone who has constantly been in spaces where knowledge is produced—whether as a student at different levels of schooling, as a teacher, or as a worker in various establishments where knowledge production is paramount—I have reflected on how we live in a world driven by academic achievement yet significantly lacking in emotional intelligence. I have witnessed the worst attitudes, to the detriment of people’s emotions, being displayed in academic spaces—the so-called citadels of knowledge production where you would expect people to be civil and humane.

How do you explain a professor who comes to class and, for whatever gratification it brings them, bad-mouths and undermines a colleague in front of their students?

How do you explain students who treat their peers with disrespect, mocking their presence and contributions in class because of the color of their skin or their accent, driven by the misguided belief that they are somehow superior?

How do you describe professors who face constant rejection because their research challenges established canonical practices in their discipline, leading to the possibility of losing their jobs and, by extension, their identity?

How do you explain a student who lies and goes out of their way to undermine their instructor just to gain sympathy and secure their grades?

How do you explain institutions that use DEI initiatives as a marketing tool while failing to provide genuine support, resources, or representation for their students of color?

How do you explain a reviewer who strikes out your sentences and replaces your words with their own, not because of clarity or correctness, but because your voice and perspective don’t align with their narrow expectations of the discourse?

How do you account for the lack of resources available to parents, both moms and dads, who struggle with the demands of graduate school while earning meager wages and paying exorbitant fees for childcare?

How do you explain people who recoil as they walk around you and handle objects you give them with only the tips of their fingers, avoiding contact with your colored skin, yet openly kiss their dogs? How do you explain the psychological implications of such behavior, suggesting they consider their pets more human than you?

How do you explain those who clutch their belongings tighter or avoid sitting next to someone based solely on their skin color, yet deny having any racial prejudice?

How do you explain those who insist on pronouncing names incorrectly and refuse to make an effort to learn, dismissing it as “too difficult,” or going to the extent of giving the person a new name that they find more convenient or comfortable?

How do you explain individuals who interrupt others to dominate conversations, showing no interest in listening or understanding different perspectives?

How do you explain those who refuse to acknowledge or validate others’ experiences simply because they don’t align with their own beliefs?

How do you explain colleagues who use passive-aggressive remarks or sarcasm to undermine others instead of engaging in honest communication?

How do you explain leaders who fail to recognize the mental and emotional strain of their team members, pushing them to meet deadlines without offering support or understanding?

How do you explain people you have always helped and been kind to, who, the one time you don’t do what they want, go out of their way to criticize or undermine you?

How do you explain senior professors who receive higher pay for doing less work, while piling responsibilities onto their junior colleagues, justifying it by saying, “That’s how it was during our time too”?

How do you explain those who judge others’ lifestyles, choices, or backgrounds without taking the time to learn about the circumstances or challenges they face?

How do you explain people who respond to others’ success with envy or resentment instead of celebrating their accomplishments?

How do you explain individuals who trivialize or mock cultural practices and traditions that are different from their own, branding them as “weird” or “unnecessary”?

How do you explain someone randomly touching your hair and saying it’s beautiful when they don’t even consider how invasive and uncomfortable such an action can be, reducing your personal space to a mere curiosity?

How do you explain someone who refuses to apologize, even when they know they’ve hurt another person, because they believe admitting fault is a sign of weakness?

How do we make sense of all of this? (Feel free to continue the myriad of “how do you explain” examples in the comments.)

Leave a comment