In my PhD journey in the Rhetoric and Writing Program, New Materialism has emerged as one of my favorite theories. Of all the scholarly discussions surrounding this theory, Nietzsche’s On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense (2005) remains a key touchstone for me. In this work, Nietzsche argues that humans often believe their perception and judgment of the world is the only valid one, which is neither fair nor true. Recalling Nietzsche’s ideas encourages me to remain open-minded, to think beyond our human-centric viewpoint, and recognize that there’s far more to the world than what we typically consider. By embracing this perspective, we can begin to see the diverse forces and energies that shape our lives, extending beyond the familiar. This mindset applies not just to academic study but also to how we reflect on the daily pretenses and lies we create to sustain our worldview.

While some may see New Materialism as anti-anthropocentric because it challenges the human ego, I align with Gruwell’s (2022) argument that it is less about rejecting humanity and more about recognizing the coexistence of human and nonhuman objects. Gries, in her book Still Life with Rhetoric, underscores the importance of acknowledging the agency and vitality of nonhuman entities in shaping our world. She argues that traditional, human-centered perspectives often fail to account for the intricate networks of interaction between human and nonhuman actors that drive rhetorical transformation and consequence. Gries’s perspective ultimately shifts how we engage with the world around us.

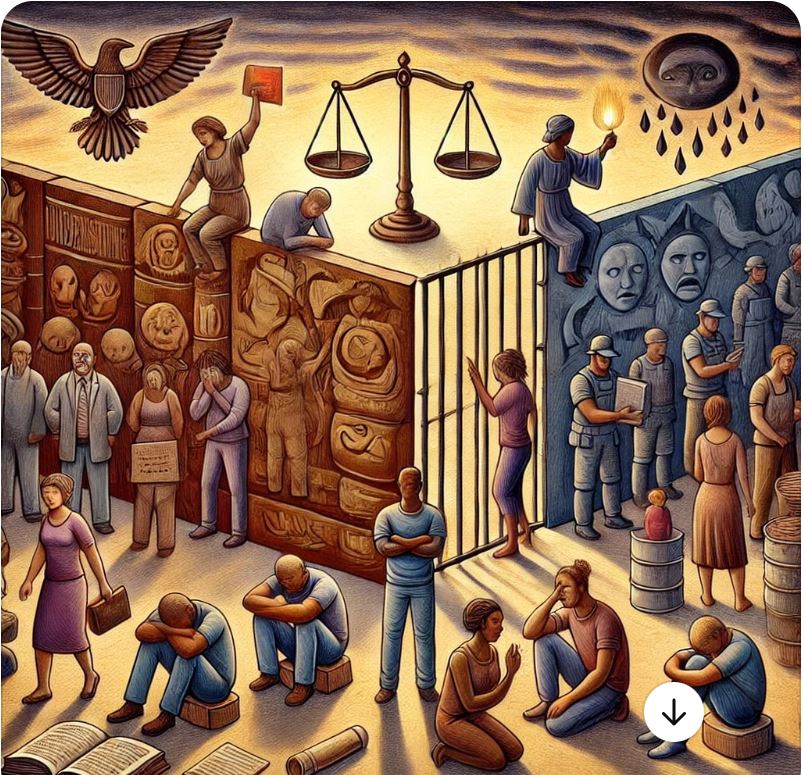

In light of this, it’s exhausting to witness the rampant materialism that pervades society today. Vanity is everywhere: in looks, clothes, cars, mansions, academic and professional achievements, race—everything. Sometimes I wonder if we ever pause to consider what ends it all: Death. Both a curse and a blessing, this non-human player strips away the illusions of material importance, reminding us of our shared mortality and the fleeting nature of everything we hold dear. It recalls Bennett’s (2010) concept of “vital players” and brings to mind the Nigerian proverb, “One day, the bush meat will catch the hunter.” At some point, the power dynamic shifts, and humans, once the players, become the ones being played. Beneath all that material superficiality, what truly remains? Do the bones of the rich turn to gold while those of the poor become sand? I often think about the transformation of once-cherished bodies through death: how the skin and organs dissolve, leaving behind only bones. If we were to place those bones side by side, could we distinguish who was rich or poor, Black or white, beautiful or ugly? It’s all just a façade, a meaningless nothingness.

If we focused less on materialism and reflected more on how we are all debtors living in a loaned world—unaware of when the creditor will demand payment—perhaps we would deflate our exaggerated sense of self-importance. Maybe then, we would become kinder, more reflective, more empathetic, and more willing to step down from our borrowed high horses.

Works Cited

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Gries, L. E. (2015). Still life with rhetoric: a new materialist approach for visual rhetorics. Utah State University Press.

Gruwell, L. (2022). Craft agency: An ethics for new materialist rhetorics. In Making matters: Craft, ethics, and new materialist rhetorics (pp. 13-39). University Press of Colorado.

Leave a comment